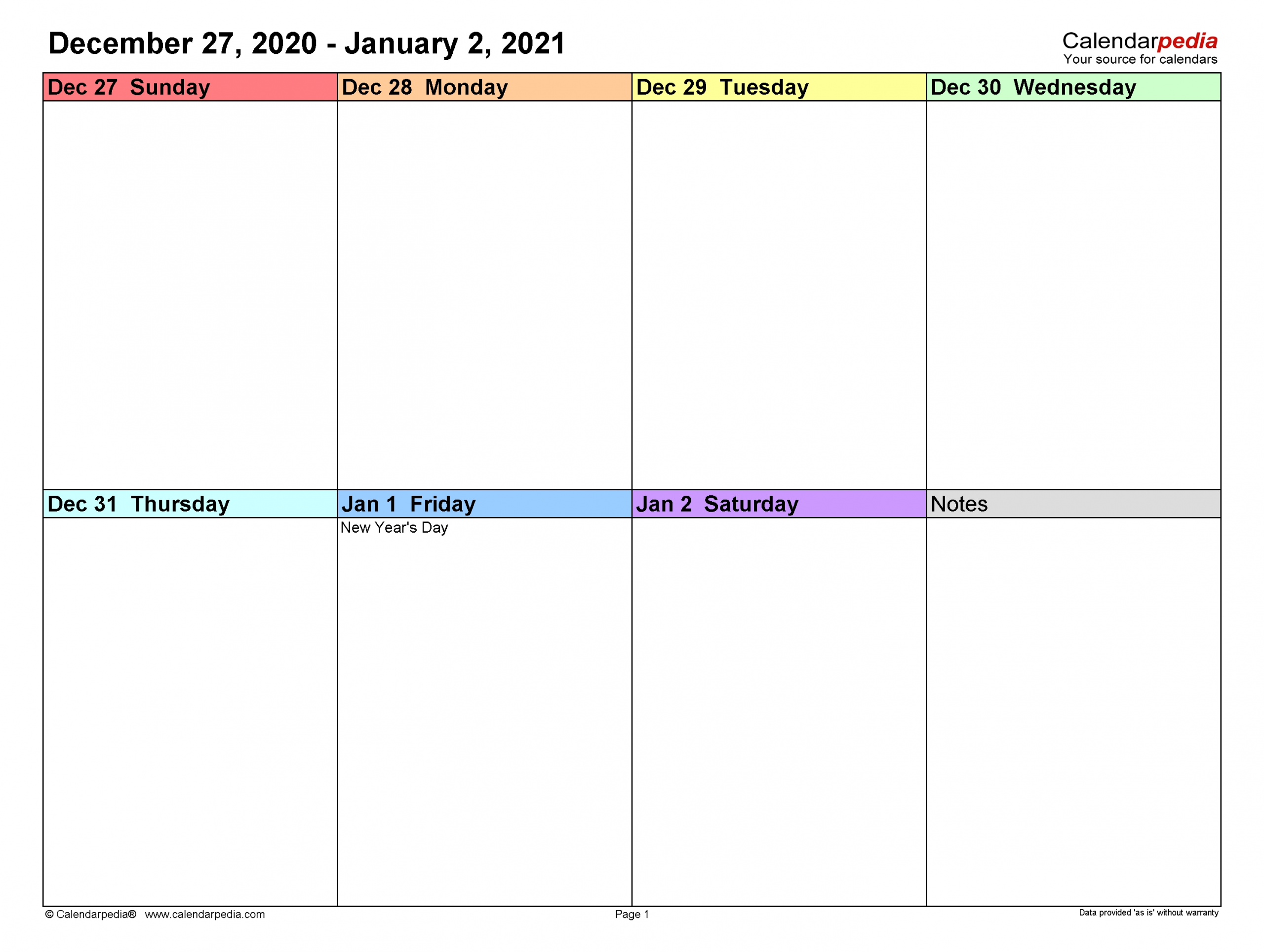

What should the calendar look like, both inside and out? What type of paper will you use? How will you bind the book? (With glue in the case of the calendar.) Should you outsource the design or do you know someone who can do it? (Yes, team member Gerard). The students discovered that publishing a book – because that’s what a calendar is in printing terms – is hard work. Where to put all those boxes of calendars.? Until they hit the magic number of 365 and everyone was content.

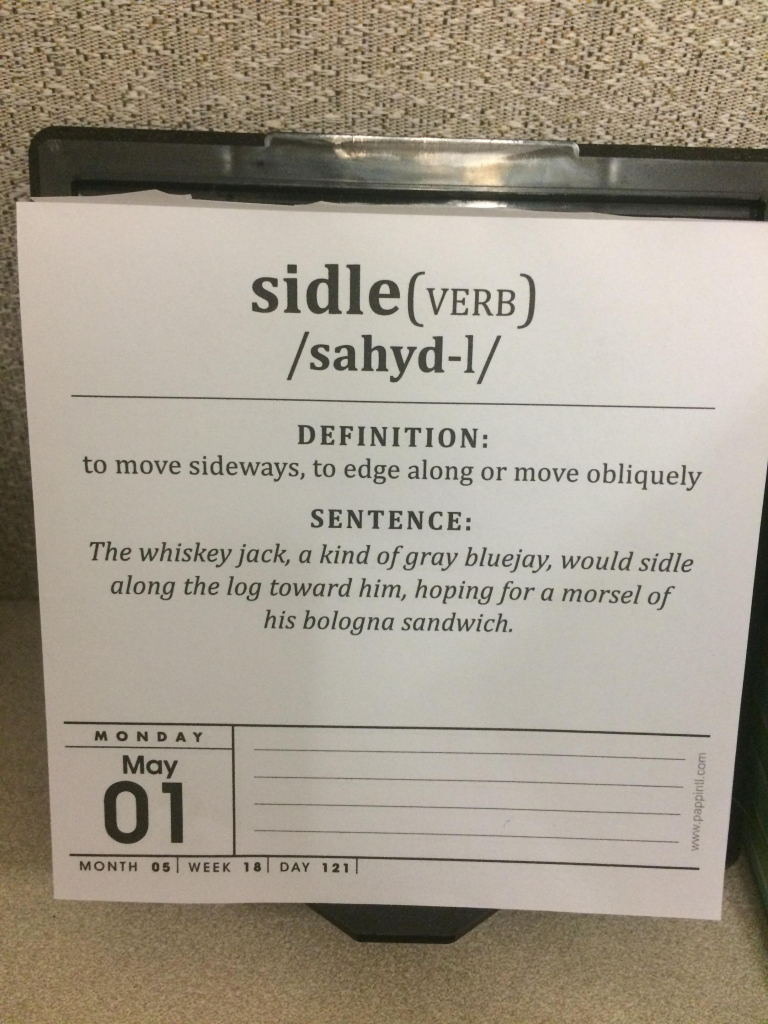

They pondered and deliberated, scrapped some examples and filled the gaps with new ones. It was a conscious decision to use not only English or Dutch words but also words from a whole range of languages. As they didn’t yet have 365 of them, they scoured their books and hit the library to find more. Last year, they put their heads together and shared the words that they already had. Reason enough for a repeat performance this year, but then in Dutch because some people hadn’t been happy with the English version. The calendar was a resounding success therefore. The students ended up printing 600 copies of the 2019 calendar, and ordering a further 135 copies later. But when their lecturers and fellow students heard what they were up to, the Excel sheet that Laura used to keep track of orders practically exploded. They decided to produce 150 copies of the calendar. So they decided to make their own, in English because that is the language of instruction in their specialisation of Comparative Indo-European Linguisticsand more or less of the linguistics programme itself. What is more, they had already seen language calendars, but weren’t particularly impressed with them. They realised that they weren’t the only ones to like language. Some of them collected words with unusual roots or words from different languages that prove to have the same roots if you go back far enough. Linguisticsstudents Pascale Eskes, Vera Zwennes, Lotte Meester, Laura Dees, Ivo Boers and Gerard Spaans knew that the etymology – or origin – of words in various languages can be strange, interesting or funny. Some sources allege that quirītāre is instead a frequentative form of the verb querī “to complain” (the source of quarrel and querulous), while others connect quirītāre to quirrītāre “to grunt (as a boar).” However, Latin may not be involved at all crier could derive instead from a Frankish source cognate to Dutch krijten “to cry” and German kreischen “to shriek.” Descry was first recorded in English in the late 13th century.One example: where does the Dutch word ‘maat,’ as in ‘mate,’ come from?

The traditional story is that crier ultimately comes from the Latin verb quirītāre “to cry out in protest,” a verb said to be related to the noun Quirītēs “citizens of Rome,” though this connection may be folk etymology and therefore based on mere coincidence. From here, there are at least four hypotheses regarding the origin of crier.

While describe comes from Latin scrībere “to write,” descry and the related verb decry both come from Old French crier “to cry,” the source of English cry. Descry “to see by looking carefully” may look and sound like describe, but the two are not related.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)